The

unveiling of a 4,000-year-old civilization calls into question conventional

ideas about ancient culture, trade, and religion.

Viktor

Sarianidi, barefoot at dawn, surveys the treeless landscape from a battered

lawn chair in the Kara-Kum desert of Turkmenistan. "The mornings here are

beautiful," he says, gesturing regally with his cane, his white hair wild

from sleep. "No wife, no children, just the silence, God, and the

ruins."

Viktor

Sarianidi spends nearly half of every year digging in Turkmenistan's Kara-Kum

desert.

Courtesy of

Kenneth Garrett

Where

others see only sand and scrub, Sarianidi has turned up the remnants of a wealthy

town protected by high walls and battlements. This barren place, a site called

Gonur, was once the heart of a vast archipelago of settlements that stretched

across 1,000 square miles of Central Asian plains. Although unknown to most

Western scholars, this ancient civilization dates back 4,000 years—to the time

when the first great societies along the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, Indus, and

Yellow rivers were flourishing.

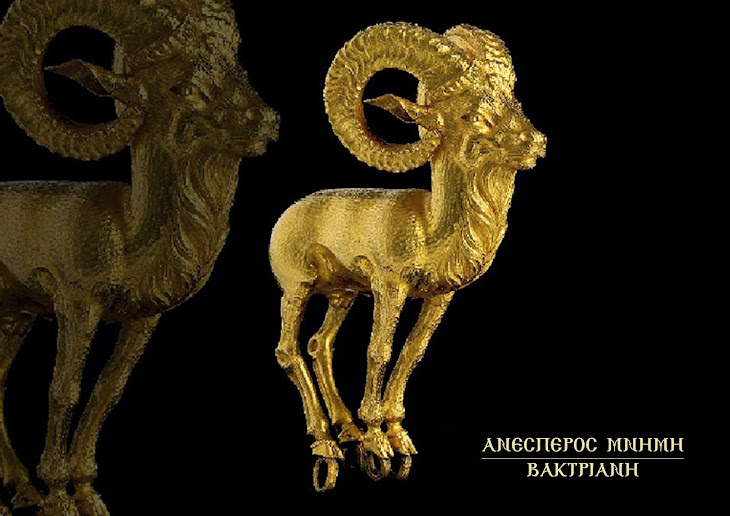

Thousands

of people lived in towns like Gonur with carefully designed streets, drains,

temples, and homes. To water their orchards and fields, they dug lengthy canals

to channel glacier-fed rivers that were impervious to drought. They traded with

distant cities for ivory, gold, and silver, creating what may have been the

first commercial link between the East and the West. They buried their dead in

elaborate graves filled with fine jewelry, wheeled carts, and animal

sacrifices. Then, within a few centuries, they vanished.

News of

this lost civilization began leaking out in the 1970s, when archaeologists came

to dig in the southern reaches of the Soviet Union and in Afghanistan. Their

findings, which were published only in obscure Russian-language journals,

described a culture with the tongue-twisting name Bactria-Margiana

Archaeological Complex. Bactria is the old Greek name for northern Afghanistan

and the northeast corner of Iran, while Margiana is further north, in what is

today Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Through the region runs the Amu Dar'ya

River, which was known in Greek history as the Oxus River. Western scholars

subsequently used that landmark to dub the newly found culture the Oxus

civilization.

The initial

trickle of information dried up in 1979 when the revolution in Iran and war in

Afghanistan locked away the southern half of the Oxus. Later, with the 1990

fall of the Soviet Union, many Russian archaeologists withdrew from Central

Asia. Undeterred, Sarianidi and a handful of other archaeologists soldiered on,

unearthing additional elaborate structures and artifacts. Because of what they

have found, scholars can no longer regard ancient Central Asia as a wasteland

notable primarily as the origin of nomads like Genghis Khan. In Sarianidi's

view, this harsh land of desert, marsh, and steppe may instead have served as a

center in a broad, early trading network, the hub of a wheel connecting goods,

ideas, and technologies among the earliest of urban peoples.

Courtesy of

Kenneth Garrett

Harvard

University archaeologist Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky believes the excavation at

Gonur is "a major event of the late 20th century," adding that

Sarianidi deserves credit for discovering the lost Oxus culture and for his

"30 consecutive years of indefatigable excavations." To some other

researchers, however, Sarianidi seems more desert eccentric than dispassionate

scholar. For starters, his techniques strike many colleagues as brutish and

old-fashioned. These days Western archaeologists typically unearth sites with

dental instruments and mesh screens, meticulously sifting soil for traces of

pollen, seeds, and ceramics. Sarianidi uses bulldozers to expose old

foundations, largely ignores botanical finds, and publishes few details on

layers, ceramics, and other mainstays of modern archaeology.

His

abrasive personality hasn't helped his cause, either. "Everyone opposes me

because I alone have found these artifacts," he thunders during a midday

break. "No one believed anyone lived here until I came!" He bangs the

table with his cane for emphasis.

Sarianidi

is accustomed to the role of outsider. As a Greek growing up in Tashkent,

Uzbekistan, under Stalinist rule, he was denied training in law and turned to

history instead. Ultimately, it proved too full of groupthink for his taste, so

he opted for archaeology. "It was more free because it was more ancient,"

he says. During the 1950s he drifted, spending seasons between digs unemployed.

He refused to join the Communist Party, despite the ways it might have helped

his career. Eventually, in 1959, his skill and tenacity earned him a coveted

position at the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow, but it was years before he

was allowed to direct a dig.

The ancient

Oxus culture may have arisen at sites like Anau, a settlement at the base of

the Kopet-Dag mountains, which dates back to 6500 B.C. Later settlements like

Gonur, roughly 4,000 years old, may have been founded by people from the

Kopet-Dag cultures.

An apparent

royal burial site at Gonur contains luxury goods, a cart with bronze-sheathed

wheels, and the remains of a camel.

An American

team works at Anau, in the foothills of the Kopet-Dag mountains.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου